Friday, December 05, 2025

The foundation is the single most important element of any structure. In cold climates like Calgary, placing concrete during the winter months introduces a layer of complexity—and risk—that far exceeds standard summer construction. When the ground is frozen, that frozen moisture becomes a hidden, structural time bomb known as frost heave.

Rushing foundation work in freezing temperatures is a guarantee of future failure. Cracks that appear years later are almost always the result of differential settlement caused by inadequate subgrade preparation during the cold season.

This comprehensive guide is designed for builders, developers, and informed homeowners, providing the advanced, technical protocol necessary to ensure your foundation is poured onto a stable, dry, and warm base, protecting your multi-million dollar investment from the damaging effects of cold weather and guaranteeing the longevity of your structure.

I. Introduction: The High Cost of Cold-Weather Mistakes and Structural Compromise 🥶

Successful winter concrete placement is a calculated scientific process, not a race against the clock. The entire protocol hinges on controlling the temperature and moisture within the ground and the concrete mix.

A. The Mechanics of Failure: Frost Heave and Differential Settlement

Frost heave occurs when three simultaneous conditions are met: frost-susceptible soil (silt/clay), sub-zero temperatures, and accessible groundwater.

- Ice Lenses: As groundwater is drawn up through the soil by capillary action, it freezes into horizontal layers of ice known as ice lenses. These lenses are incredibly powerful, expanding vertically and lifting the ground with tons of pressure.

- The Unavoidable Thaw: When spring arrives, these ice lenses melt, leaving voids in the soil. The unsupported concrete above then settles unevenly (differential settlement). Since concrete is rigid, this uneven movement causes shear stress, resulting in the deep, structural cracks that compromise the foundation’s water resistance and structural integrity.

B. The Absolute Protocol: Above $0^\circ\text{C}$ ($32^\circ\text{F}$)

The core rule of cold-weather concreting, mandated by codes like CSA A23.1/23.2 in Canada, is that the fresh concrete must be protected from freezing until it reaches a minimum specified strength (typically $500 \text{ psi}$ or $3.5 \text{ MPa}$).

Crucially, this protection must extend below the pour. If the subgrade temperature is below $0^\circ\text{C}$, the fresh concrete will rapidly lose its hydration heat to the frozen ground, significantly slowing strength gain and increasing the risk of early-age freezing and permanent strength reduction.

II. Phase 1: Subgrade Assessment, Excavation, and Geotechnical Verification 🔬

The work begins with advanced site analysis, particularly important for complex infill or multi-family projects where existing soil conditions are often unpredictable.

A. Geotechnical Due Diligence and Water Control

A detailed Geotechnical Report is not optional; it is mandatory for complex winter pours.

- Soil Susceptibility: Identify the percentage of fines (silt and clay) in the soil. High fines content indicates high susceptibility to capillary action and frost heave.

- Dewatering Strategy: If the water table is high, the site must be effectively drained and potentially dewatered (using well points or trenches) to reduce the saturation level of the subgrade. Dry soil is far less susceptible to frost heave than saturated soil.

- Excavation Depth and the Frost Line: Footings must be excavated below the regionally mandated frost penetration depth to prevent lateral frost action from undermining the foundation walls. This depth is non-negotiable and dictated by local codes.

B. Verification of Non-Frozen Status

Visually inspecting the subgrade is insufficient. The temperature of the ground must be confirmed.

- Thermal Verification: The builder must use infrared thermometers or temperature probes to confirm the subgrade is uniformly above $0^\circ\text{C}$ ($32^\circ\text{F}$) for at least $300 \text{ mm}$ (12 inches) below the footing line.

- Removal of Frozen Material: All visible snow, ice, and frozen clods of earth must be completely stripped from the subgrade, ideally using compressed air, mechanical removal, or manual scraping. Never use chemical de-icers (salts) as they contaminate the soil and can chemically attack the concrete over time.

III. Phase 2: Thawing, Heating, and Stabilization (The Science of Thermal Management) ♨️

This phase requires specialized equipment and a calculated thermal management plan. Rushing the thaw is the fastest way to invite future cracking.

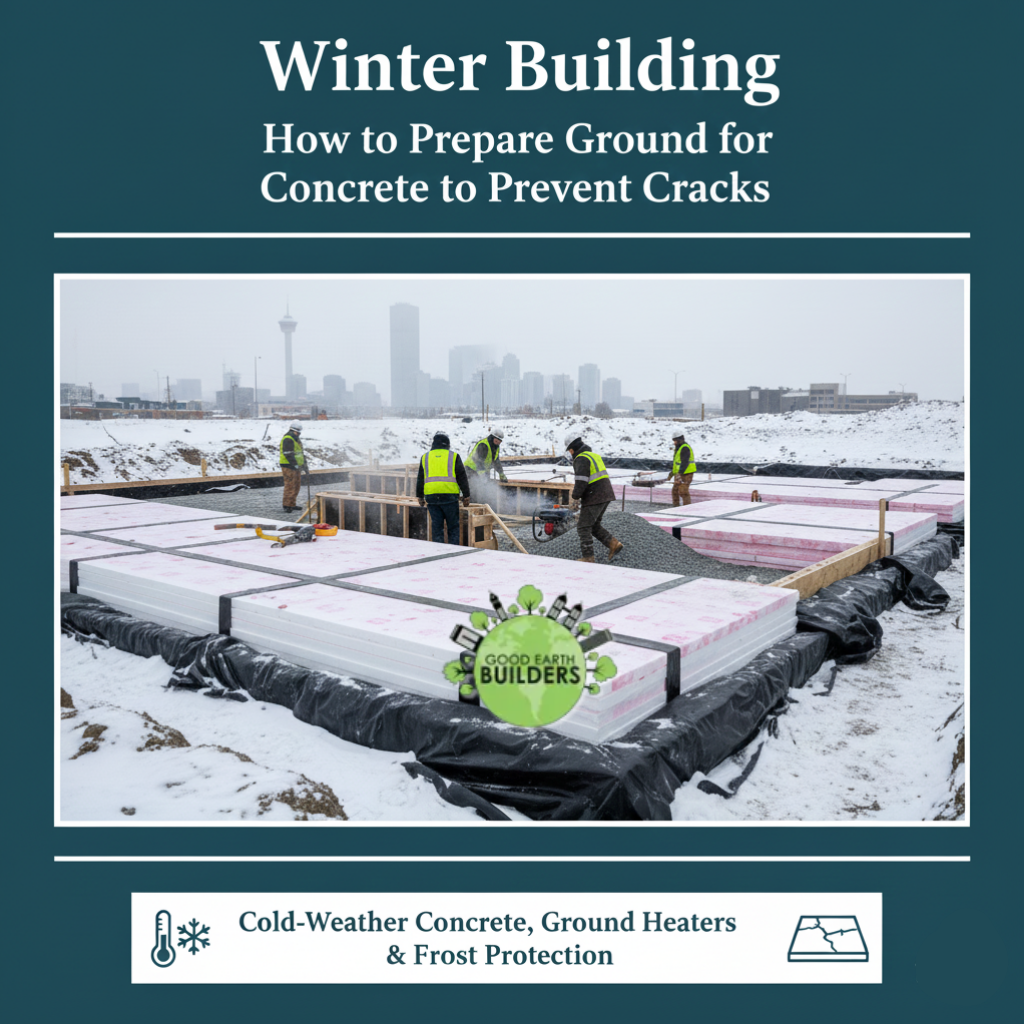

A. The Gold Standard: Hydronic Thawing Systems

For large-scale projects and deep frost, general heating is inefficient. Direct, calculated heat application is required.

- Hydronic Heaters: These systems circulate heated glycol (antifreeze solution) through a network of hoses laid directly over the ground and covered by thermal blankets.

- Benefit: They provide deep, even, and consistent heat distribution that penetrates the subgrade uniformly. This minimizes the risk of uneven thawing and subsequent differential settlement.

- Electric Thawing Blankets: Suitable for smaller, shallower areas. They provide targeted heat but require careful placement and monitoring to prevent hot spots.

- Thaw Time Calculation: Thawing is slow. A general rule of thumb is that it takes approximately 1 to 3 days of continuous, controlled heat application for every 300 mm (1 foot) of frozen ground depth, depending on ambient temperature and soil type. This preparation time must be accounted for in the contract schedule.

B. The Aggregate Base and Vapor Control

Once thawed, the subgrade must be immediately prepared with a stable, dry buffer layer.

- Granular Base Layer: A minimum 150 mm (6 inches) layer of clean, non-frost-susceptible granular aggregate (crushed rock or clear stone) is installed. This layer provides rapid drainage and distributes the load evenly.

- Compaction Verification: The thawed subgrade and the aggregate layer must be compacted using vibratory equipment. Professional builders verify the density using a Nuclear Density Gauge or a Proctor Test. This data provides objective proof that the base can bear the structural load without settling.

- Vapor Barrier (The Membrane): A minimum 6-mil polyethylene vapor barrier must be installed over the base layer. This prevents moisture from the underlying ground from rising into the slab, which protects the concrete’s curing process and prevents future interior humidity issues. It also stops the essential water in the fresh concrete from wicking into the dry subgrade.

IV. Phase 3: The Concrete Mix and Chemical Defense 🧪

Since the concrete itself is at risk of freezing, the mix design must be modified using chemical agents that act as a cold-weather defense.

A. Admixtures: The Chemical Accelerator

Concrete must achieve $3.5 \text{ MPa}$ of compressive strength before it is allowed to freeze. Admixtures accelerate this process.

- Non-Chloride Accelerators (NCA): These chemicals, typically calcium nitrate-based, accelerate the hydration reaction, causing the concrete to gain strength much faster. Non-chloride formulas are mandatory because chloride accelerators can lead to the corrosion of steel reinforcing bars (rebar) embedded in the concrete.

- Air-Entrainment: This is crucial for durability. Entrained air creates microscopic, disconnected air voids within the concrete mix. When water inevitably penetrates the concrete and freezes, it expands harmlessly into these tiny voids instead of cracking the structure. All exterior concrete in cold climates must be air-entrained.

- Increased Cement Content: Often, the concrete mix is designed with a higher cement content (e.g., a $40 \text{ MPa}$ mix instead of a standard $30 \text{ MPa}$ mix) to increase the rate of hydration, which generates more heat internally.

B. Formwork, Enclosure, and Temperature Monitoring

The final protection is a controlled, heated microclimate around the fresh pour.

- Rigid Insulation: Rigid foam insulation (XPS) must be installed vertically around the perimeter of the forms. This prevents rapid heat loss from the slab edges, which are the most exposed and vulnerable areas.

- Temporary Heated Enclosure: A robust, framed enclosure must be built over the foundation. This structure, often covered with heavy tarps, maintains an ambient air temperature above $10^\circ\text{C}$ ($50^\circ\text{F}$) throughout the 7-day initial curing period.

- Vented Heating is Mandatory: Only vented, indirect-fired heaters should be used. Unvented heaters release combustion byproducts (carbon dioxide and water vapor) into the enclosure, which can lead to carbonation (weakening the surface) and severe moisture/mold risk.

V. Phase 4: Curing, Stripping, and Post-Pour Verification 📊

The curing process dictates the concrete’s final strength. A good builder bases decisions on objective data, not elapsed time.

A. Strength Verification (The Test Cylinders)

In cold weather, the time it takes to reach full strength varies dramatically.

- Test Cylinders: Multiple concrete cylinders are poured from the same batch as the foundation. These cylinders are cured on-site in the same conditions as the foundation (in the heated enclosure).

- Stripping Protocol: Formwork (the wooden structure holding the concrete) should only be removed (stripped) once the test cylinders confirm the concrete has reached the specified minimum strength (often $10 \text{ MPa}$ for safe form removal). Waiting an arbitrary number of days is unreliable in cold conditions.

B. Gradual De-Heating and Thermal Shock Prevention

Rapid cooling causes immediate, surface-level cracking (thermal shock) due to the difference between the core temperature and the surface temperature.

- Controlled De-Heating: The insulated enclosures and heaters must be removed slowly and in stages. The temperature of the concrete surface should not be allowed to drop by more than $2^\circ\text{C}$ ($3.6^\circ\text{F}$) per hour during the cool-down period.

- Post-Cure Protection: After the forms are stripped and the enclosure is removed, the concrete surface should remain covered with thermal blankets for several more days to ensure the deeper core continues its slow strength gain.

VI. Conclusion: Building on a Foundation of Certainty and Integrity ✅

Building a foundation in a cold climate is a highly technical, multi-stage process that requires a builder to master geotechnical engineering, thermal dynamics, and chemical material science. Cutting corners at any point—whether by skipping ground thawing or using unvented heat—is a direct trade-off that compromises the longevity and value of the entire structure.

By demanding this rigorous, scientifically verified protocol, you move your project from the realm of risk to the realm of certainty.

Building on a Foundation of Certainty: The Good Earth Builders Difference

At Good Earth Builders, our reputation in the Calgary market is built upon the integrity of our foundations, regardless of the season. We view the winter months not as an obstacle, but as an opportunity to demonstrate superior technical expertise.

Our cold-weather foundation protocol includes:

- Mandatory Hydronic Thawing: We deploy advanced hydronic systems to ensure deep, precise subgrade warming, guaranteeing a stable base.

- Customized Concrete Mix Design: We partner with certified suppliers to design concrete mixes with accelerators and air-entrainment optimized for the specific ambient temperature of the pour day.

- Objective Strength Verification: We manage on-site test cylinders and utilize objective lab data to determine the exact moment formwork can be safely stripped, preventing premature loading stress.

- Long-Term Durability: Our focus on meticulous curing and thermal shock prevention guarantees a durable, crack-resistant foundation that exceeds the minimum 10-year warranty requirements.

Don’t let the pressure of a winter schedule compromise the long-term integrity of your home. Invest in a builder who uses science and precision to secure your foundation against the relentless Calgary cold.

📞Contact Good Earth Builders today to discuss our cold-climate construction standards and receive a transparent breakdown of the protocols that ensure your custom home foundation will stand the test of time and temperature.